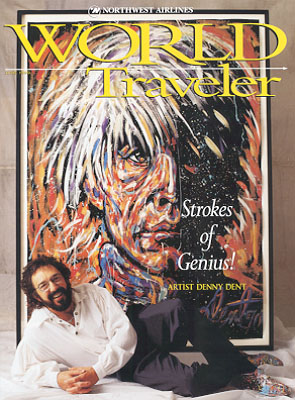

Masterpiece Theater

Masterpiece Theater

By Tina Lassen - Photographs by Danny Turner and Larry Laszlo

"People ask me what I want to say to artists," says performance artist Denny Dent. "But they are thinking only of 'painters.' Everyone is an artist. Love what you do. If you're enjoying your life, you're fulfilling something within."

DENNY DENT is about to start painting. Picture him in his studio, a battered easel propped before him, maybe a little soft music in the background. Solitude. Reflection. Musing and waiting for the glimmer of an idea that will carefully translate into a brushstroke on canvas.

Now picture how it really happens: Dent strolls onto a stage in a paint-splattered tuxedo. An audience of hundreds - sometimes thousands or hundred of thousands - murmurs and twitters. "Foxy Lady" thunders out of a sound system and Dent lurches into action. He turns his back to the crowd and toward a six-foot canvas and the buckets of paint lined up below it. And the dance begins. Dent twirls and leaps in time with the music, slashing broad swaths of paint, three brushes in his left hand, three brushes in his right.

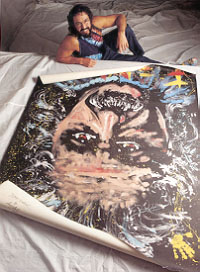

"Foxy Lady" fades out and "Purple Haze" begins. Dent picks up his frenzied pace, leaping and spinning. His face is contorted, his eyes in a wildfire trance. But more and more, the audience turns their gaze from Dent to his canvas. What looked like abstract is now segueing into shape: A broad stroke of paint suddenly reveals the unmistakable profile of Jimi Hendrix.

"Purple Haze" ends seven minutes and 37 seconds into Dent's performance. He is transfixed. Dent abandons his brushes and grabs handfuls of paint, splattering it in a spray of color across the painting, now a clear, brilliant portrait of Jimi Hendrix. He leaps in a frenzied crescendo as the song reaches its climax, shouting and hurling color. The final chord sounds, precisely as Dent stamps his handprint Signature. He turns to face his audience, exhausted but exhilarated. They are stunned. Silent. Then as if on cue, they leap to their feet in a single wave.

"Denny Dent and his Two-Fisted Art Attack," goes the official title of Dent's performance art show. "Describing the Art Attack to someone who has never seen it can be like describing a rainbow to someone who cannot see," declares his promotional materials. "You must experience it live in order to understand. Only then can you truly count yourself among the initiates. Only then will you truly understand the importance of the Art Attack."

Dent himself offers up a simpler description. "It's a dance on canvas," he says. It's a phrase he's used many times before, one that clearly pleases him. Still, he paces and flutters his hands in an attempt to attach more words. With long curly black hair and a dark, thick beard, Dent comes across just as animated offstage as on, but with a noticeably gentler soul. "People ask me, 'Are you a performer or an artist?'" he adds after a minuscule pause. "Well, I'm a performance artist. The art needs to be good enough to stand on its own, but the performance is the art form."

Call it what you will, Dent has uncorked his energy and talent hundreds of times, at conventions and street fairs, at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and President Clinton's inauguration. He claims Denver as his home, primarily to live near an area of the country where he can reduce his time on the road, which tallies up to more than 100 days per year.

He's painted Jimi Hendrix while searing guitar music blared across the loudspeakers at Woodstock '94. He's painted Beethoven while accompanied by a symphony orchestra. He has performed at shows as diverse as the Olympics and the ballet. He's painted Martin Luther King Jr. to gospel music and excerpts from his "I have a dream" speech. Dent's portrait of King is hanging in the Civil Rights Museum and the King Center in Atlanta.

All are done to music, all completed in mere minutes. The Guinness Book of World Records even wanted to record Dent as the world's fastest painter. But to focus on the speed - or even the painting - is to miss the whole point, suggests Dent. In fact, Denny Dent may be the only artist in the solar system who refers to his paintings as a "by-product" of his art.

"It isn't about painting," he insists as he's ushered to a table in his favorite Italian restaurant. "The painting is the platform. It's showing people something different. It's getting them to think a different way."

Dent's art, in essence, is to expand the very definition of art. To expand the very notion of creativity. "It's not what you do, but the way you do it," he stresses, the words tumbling out even faster. "People say, 'But I can't draw a straight line.' Well, neither can I. It doesn't matter. You can be a great craftsman, and not put a breath of life into your work.

"Art is all about loving something. It's an expression from the heart. The vehicle doesn't matter. It's that you put a spark - your own spark - into it."

Dent begins each performance with a talk. "It's all about creativity, about the artist inside of everybody," he explains again, almost pleading for you to grasp this oh-so-vital concept. "I have a wonderful blessing of being able to communicate with people. I'm no professional speaker. Sometimes the words come out clumsy. But I make the connection."

He says this last sentence slowly, as slowly as he possibly can speak, even pausing to take a bite out of his untouched pasta lunch. "But that doesn't matter. You can stumble around, mispronounce words or whatever. If it's from the heart, it lands on the heart. And what I say is from the heart. The greatest gift I have is the ability to touch people and encourage them to be creative."

Dent's early Art Attack shows played primarily to college students. He performed at more than 75 universities a year in the early '80s, and twice won Performance Artist of the Year from the National Association of College Activities. For young people just discovering who they were, stretching and testing and trying new things, the message was a natural.

Then corporations began hearing about Dent's performances and began calling. "I was afraid of it," he admits. "I was used to colleges, the streets. I thought, 'These are the people who didn't want me to hang out with their sons or go out with their daughters.' I just painted and got out.

"One day I realized these people were all younger than me. Then it suddenly hit me - these were their sons and daughters. And they're hiring me!" He laughs conspiratorially. "They're wonderfully fertile ground. They want to be sparked by this. It was my own prejudice," he adds, delighted at the thought of expanding his own vision.

Dent was born in Oakland, California, to a family of artists. "My grandfather was ambidextrous," he says, giving a nod to the gene pool for his two-fisted talents, "a cabinetmaker and an artist. My mother was a painter and always told me I was an artist. That's the heritage of the family." Though no one's been able to verify it, Dent's grandfather insists they are direct descendants of Titian, the Renaissance Italian master.

No matter how far back his memory takes him, Dent cannot remember a life without art. "I was always painting," he says simply. "I painted with my hands, with my feet. I never thought of art as having anything to do with my hands. In fact, it didn't have anything to do with paint." The seeds had been planted, but it would be years before Dent would figure out exactly what he was sowing.

Then again, sticking to any story line can be a challenge with Dent. He gleefully leaps from one topic to another, his mind racing as rapidly as his fingertips across a canvas. One minute, he's talking about his childhood; the next millisecond, he's on to his vitamin regimens and his vegetarian diet. A discussion about his performances suddenly veers off into Warhol. Or the best cough drops. Or the family of rabbits living in the backyard. Or the collection of toy bunnies that fills a room in the Denver home he shares with Ali - and the fanciful tales that go along with each. Like his portraits, Dent's conversations surprise, delight and blur the line between reality and fantasy.

Lassoed in for the moment, Dent returns to his story. In December 1981, while living in Las Vegas, Dent heard about a vigil a local radio station was organizing in a park to mark the first anniversary of John Lennon's death. Dent attended and told the promoters he wanted to paint. Though somewhat puzzled, the station relented. To hear it described by Dent - an enormous admirer of Lennon - the evening was pure magic.

"I'd never been on a stage in my whole life," he says mystically. "But I grabbed the microphone and words just started coming out." Then, with Lennon's music sifting over the growing crowd, Dent began painting. A young John Lennon took shape. To Dent, who always painted with music, it was a fitting tribute - a way to pay his respects to Lennon, a way to express his feelings of anger and sadness at the loss.

But he wasn't at all prepared for the reaction of the onlookers. "Pandemonium broke loose," he marvels. "Eighteen hundred people rushed the stage. And I knew this was what I was going to do with my life."

A promoter on hand asked Dent the name of his show. "Show? I don't have a show," Dent responded. The promoter dubbed it "Art Attack," and immediately hired Dent for his first paid performance: opening for Steppenwolf at the Troubadour Club in Los Angeles for $50 a night. "I was scared to death," he recalls. "But I was thinking too much about me. Once I realized that the message had nothing to do with me, the shakes went away."

Next came other bands - he opened for the B-52's, among others - then the long and successful run of college campuses. He became known as the "rock and roll artist," painting a growing repertoire of musicians that included Lennon and Jimi Hendrix (still the two he is best known for), Jim Morrison, Bob Marley, Mick Jagger, Jerry Garcia, Eric Clapton and dozens more.

Today, his performances have expanded to include nearly 100 subjects - personalities as disparate as Bill Gates, Jack Nicklaus, Albert Einstein and Garth Brooks - and his list of clients reads like a table of contents in Forbes magazine: McDonald's, IBM, Coca Cola, Harley Davidson, Northwest Airlines, Pepsi, AT&T, Hallmark Cards, MCI, Merck and Mercedes-Benz.

His show generally lasts one hour and consists of four paintings with his message of creativity interspersed. Many times Dent is commissioned to paint an original performance portrait of a CEO, athlete or celebrity. He also donates performances to a limited number of charities (Americares and Make a Wish Foundation, among others), who then auction off the portrait. Auction prices have topped $40,000.

Does he have to like the music? "You know, there was a point early in my career when I didn't want to paint someone if I felt they weren't hip," he says haltingly, not sure if this is an appropriate thing to reveal in an interview. "Well, what is 'hip' anyway? And hip to whom? I don't even have a favorite subject anymore. I have different ones at different places at different times. I realized that what I really enjoy is pleasing the crowd, driving home the message.

Behind the apparent spontaneity of Dent's work lies a considerable amount of prep time. For musician subjects, he'll listen to their work, trying to find songs with a tone he thinks will capture their spirit - and a tempo that will allow him to pace the show with drama. "When you listen to the music, on an intangible level, you begin to understand what makes up a person. And I hope that comes across in the portraiture."

For other subjects, he'll watch endless videos, or pore over as many photographs as possible. Then he'll match up appropriate music - perhaps a cowboy tune for Will Rogers, a little ragtime for Charlie Chaplin - that has the required tone and tempo.

Next come pencil sketches, then composites, then paintings, all refining a portrait that makes it clear that Dent could make a fine living as a less aerobic artist. Once he's developed a basic portrait that pleases him, he choreographs it to the music. It can take a couple days, or it can take a week. And that, of course, is just part of the recipe. Dent feeds on the audience, the moment and the energy to transform his portrait into performance art.

Even when he's not on stage, energy still swirls around Dent like a fog machine. Watching him is like watching one of those old 8mm home movies, where everything happens just slightly too fast and jerky. If it weren't so constant, you'd think it was an act: the creative, befuddled genius. But then just as he's making a point, his cell phone chirps to life, and he spends 30 Marx Brothers seconds lurching through his pockets to ferret it out. He starts his car twice, evoking hideous squeals out of the ignition. He misplaces his keys. Forgets his jacket. Exiting the restaurant, he spins around enough times in the adjacent hotel lobby that everyone present either giggles and glances away, or simply stares out of curiosity.

He would like to end his magazine interview by two o'clock, he had said on the phone a week earlier, "because then we hit my low time." Low time? If Dent's biorhythms spiked any higher, you'd have to peel him off the ceiling. It is not a far mental leap to picture him flinging paint all over the lobby of the Loews Hotel.

Along with the energy, Dent thrives on a little fear as a motivator. At more than half of his shows last year, he didn't sketch the subject ahead of time, didn't practice at all. Without choreography, that means he didn't know exactly when the music was going to end, either. His assistant simply stood alongside the stage, signaling how many minutes remained. The performances weren't just dances, they were down-to-the-wire races.

"Nothing has failed yet, but I'm flirting with disaster," Dent says, with a mischievous grin on his face. "I sweat like a kid on a first date.

"I do it to myself on purpose," he says, responding to the obvious question before it's even asked. "I felt like I was losing my edge. So this puts the fear of failure in me. I go on stage with the attitude, 'If I'm going down, I'm not going down without a fight.'" Ali, he says, long ago diffused the anger that used to permeate his work; now Dent has found a way to bring back the positive part of it, the creative tension.

But what about mistakes? "There is no time for mistakes," he says at first, but then later acknowledges that you can paint over a spot once, "before it all turns to gray. Sure, there are mistakes and stuff. But it doesn't matter. It doesn't stand in the way of the message."

Back at Dent's home, he wanders through big airy rooms filled with his canvases. Some are Art Attack pieces, like an immense Elton John and a remarkable Andy Warhol. "It was the only one-hour Two-Fisted Art Attack ever," he says of the latter. "It just kept rotating and happening."

There's a dreamy, cloudy portrait of Marilyn Monroe, her piercing blue eyes practically glowing through a mist of gray; another of Albert Einstein with the painted-over bristles of Dent's brush serving as Einstein's mustache.

He picks up a canvas measuring maybe a couple square feet, a remarkable portrait collage made up of layer after layer of tissue paper. "These can go on for 20, 40, 60 hours, he says, sounding pained at the thought. "They'll glow like a stained-glass window. I have no idea how they happen."

There are lots of unfinished pieces, too, dozens of canvases propped up in hallways, piled up in the basement. Dent riffles through a few. "If I leave it, I don't come back well," he says with a shrug.

Maybe it's because those other projects don't shout "the message" from the rooftops. Maybe it's because nothing could ever match the adrenaline rush, the emotional blood-letting of a live Art Attack performance. Dent drifts into a description as he begins a cougarlike pace across the room.

"When the stars are right, the crowd is ready. I'm in tune. The dance is wonderful. I end on a dime. The product is beautiful. There's electricity in the air. The crowd leaps out of their chairs like Pop Tarts out of a toaster. Then you know the message has hit home." His eyes shine at the thought. "The gratification goes way beyond dollars and cents. You've touched them. You've stirred something deep inside their soul."

And you've given them much more than a painting.

And that is how Denny Dent paints.

And that is how Denny Dent paints.

He was a rebellious kid. It's difficult to picture that now, since Dent practically seems to glow with a genuine joyfulness. "That's because of Ali Christine, the love of my life," he says. "She's the roots to my tree. None of this could have ever happened without her." Earlier in his life, though, Dent dropped out of school, drifted over to Berkeley and pretty much lived the life of a street artist in the epicenter of Sixties culture. He regrets some of it now ("I'm really a strong, strong advocate of education," he says, referring to his own truncated schooling) and shies away from it in conversation.

He was a rebellious kid. It's difficult to picture that now, since Dent practically seems to glow with a genuine joyfulness. "That's because of Ali Christine, the love of my life," he says. "She's the roots to my tree. None of this could have ever happened without her." Earlier in his life, though, Dent dropped out of school, drifted over to Berkeley and pretty much lived the life of a street artist in the epicenter of Sixties culture. He regrets some of it now ("I'm really a strong, strong advocate of education," he says, referring to his own truncated schooling) and shies away from it in conversation.

(Reprinted from Northwest Airlines World Traveler; 1999)